This is a personal story I wrote many years ago. But as I re-read it, I thought the raw story might be helpful to some folks today. This is Part 3 of 3. Part 1 ran Wednesday. Part 2 ran on Thursday.

MY BROTHER is out of the hospital now. He has been clean for several months.

Instead of going to bars after work and on weekends, he goes to hour-long AA meetings scattered throughout Akron, where AA was born in 1935. He goes every day.

He doesn’t expect to need this much support forever. But he needs it now. Sometimes he goes to two meetings each day on weekends.

When I visited Chuck recently, he asked if I wanted to go to one of the meetings with him. I went to two. The most memorable was the one at Edwin Shaw Hospital, where my brother had been treated.

There were about 50 of us in the hospital cafeteria. All kinds of people. Huge, bearded biker types. Well-dressed executive types. There was a woman in her mid-20s with a little boy she kept hugging and kissing. At the table in front of us set a frail young lady who became addicted to cough medicine. My brother told me she thought if she limited herself to cough medicine she wouldn’t become an alcoholic.

A good-looking, well-dressed, nervous young woman was the speaker for the evening.

“Hi. I’m Jill. I’m an alcoholic. For those of you who care to, help me by joining in the Serenity Prayer.”

Together we recited: “God grant me the serenity to accept the things I cannot change, courage to change the things I can, and wisdom to know the difference.”

For 45 minutes she told the story of her plunge into alcohol. Afterward the floor was open for comments.

A dark-haired woman in her 50s stood. She was Jill’s sponsor – a fellow alcoholic assigned to encourage and help her. Among the few words she spoke were these, which continue to haunt me: “All of you in this room are my friends. You’re all the friends I have.”

I felt so ashamed.

I’ve been in the church all my life. I worked as an editor in my denomination. I believe God put the church here to help hurting people. Yet I had allowed ignorance to isolate me from the deep pain of alcoholics and drug abusers. My brother included.

The room was full of cigarette smoke. Nearly everyone smoked. I hate smoke. I stay away from people smoking. But an unearthly thing happened to me during that hour. I enjoyed the smoke. As I sat there, I knew it was saturating my hair and clothes. When I would leave the hospital, the smell would leave with me.

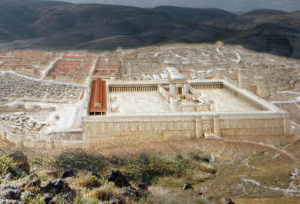

But I felt like I was in the Temple of God when the priests burned their incense in the sanctuary, and it wafted upward to become a fragrant offering to God.

I felt like this was a holy place because I was where I was supposed to be, and Jesus was there with me, walking around the room, healing people in pain.

The meeting was nearly over when, in the back corner of the room, a thin and trembling black woman rose. She wore the blue hospital blouse of a patient. She must have been in her late 20s or early 30s. Her curly, shoulder-length hair was greased and pulled back tight off her forehead and released in a fray behind her head. The hair look like it had been styled by the wind during a motorcycle ride. I thought then the woman looked like the stereotype of the junkie.

“I’m an alcoholic,” she said. “I’m in withdrawal now.”

The words broke her voice, and she began to talk between gentle sobs.

“This is the first time I’ve admitted I’m an alcoholic. I’m hoping and praying God will help me. Please pray for me.”

My outward composure only hinted of the bitter weeping that exploded inside me. I wept for her. And I wept for my brother, who had stood in her place two months earlier. And for myself, because I didn’t know how to help.

In the closing ritual, common to most AA meetings, we all stood, joined hands, repeated the Lord’s Prayer, and then ended in unison, “Keep coming back.”

My brother told me to wait a minute, and he walked toward the trembling woman. I followed behind him.

He whispered words I could not hear. He told me later he said he had been through the same thing and that he had some bad days but that it gets better. Then he hugged this physically unattractive total stranger.

He stepped aside, and suddenly there I stood before her. No longer isolated from hurting people by a sanctuary, religious rites, or the fence around my suburban yard. There was just me – the never-rebellious, lifelong churchgoer – standing face-to-face before an alcoholic in the agony of withdrawal. I saw weariness in her face, a pleading in her eyes, and tears pumping down her cheeks. She rested her hands on my back as I held her, and she laid her head on the nape of my neck.

“I’ll be praying for you,” I whispered.

“Thank you,” she replied.

I patted her back, walked away, and carried with me on the left side of my face a sprinkling of her teardrops.

As my brother and I walked to his pickup, he smiled at me, happy I had come with him. I was happy too. For I felt I had been to a church Jesus attends.

Later that weekend, I asked Chuck how he felt about his future.

“My biggest goal is to be average. I want to be like everybody else. I want to be able to deal with my problems without drinkin’ and druggin’. I want to be able to watch my kids grow up. I want to be there for my family.”

I asked our mom how she feels about Chuck’s future.

Her face took on a distant look, perhaps the very same one that day my brother pulled out of the driveway and left for the hospital. “The Lord will perfect that which concerneth me,” she said. Then she smiled.

February 1, 1989, is Chuck’s sobriety date. Of the 13 people who went through detox together at Edwin Shaw Hospital (eight men, five women) Chuck is the only one still drug-free. Chuck has married a recovering alcoholic who has been drug-free nearly as long as he has been.

thank u for sharing this story, steve.