I COULDN’T RESIST.

After I posted yesterday’s blog, Who stole John 5:4?, a friend of mine—Steve Grisetti—posted an intriguing reply. He asked about another missing part of the Bible, which survives only in the King James Version and its modern-lingo cousin the New King James Version.

This isn’t just any missing part of the Bible.

This is the ONLY part of the Bible that, clear-as-day, supports the idea of the Trinity — three Gods in one.

Without it, the best we’ve got is three Gods, not necessarily in one:

“Make disciples of all nations. Baptize them in the name of the Father and of the Son and of the Holy Spirit” (Matthew 29:19 NIRV).

But what we find in the KJV and its kin is one particular verse that rubber-stamps the Christian teaching that God is three in one.

Sadly, it’s a rubber stamp we won’t find in any other Bible.

Take a look at how verses 7-8 read from the New King James Version, compared to a couple of other versions that most scholars agree are more reliable.

Dark type in the NKJV is what’s gets the ax in the better Bibles, with apologies to the publisher of the NKJV.

“For there are three that bear witness in heaven: the Father, the Word, and the Holy Spirit; and these three are one. And there are three that bear witness on earth: the Spirit, the water, and the blood; and these three agree as one” (1 John 5:7 NKJV).

Here’s how those verses read in two other translations:

“There are three that testify: the Spirit and the water and the blood, and these three agree” (New Revised Standard Version, a scholar’s favorite).

“There are three that give witness about Jesus. They are the Holy Spirit, the baptism of Jesus and his death. And the three of them agree” (New International Reader’s Version, for kids like me).

So, what in the dickens is that bold phrase doing in the God’s Honest Truth KJV? And why isn’t it in most other Bibles?

Short answer: the KJV got it wrong.

So did the NKJV, again with apologies to the publisher who continues to provide care and nurture for those joined at the hip and the stiff upper lip with the KJV.

As Bible historians explain it, the KJV translators used an unreliable source.

It all started with a well-intentioned editor who had no idea what he was talking about.

That’s the beginning of my paraphrase of Bible historians.

Here’s more.

This editor—perhaps an ancestor of editors I could identify by name but probably shouldn’t, though I so want to—read the original Greek words and thought, “What the heck?”

They didn’t make sense. They weren’t clear enough. They needed some editorial help.

So the editor, editing his life away perhaps several centuries after John wrote the original words, added his explanation to help John out a bit.

You’re welcome, John.

The editor simply inserted what Christians believed about the Trinity, as though that’s what John was talking about in those verses.

Actually, the editor more likely added his phrase into the margin, like a note we’d find in a study Bible. If so, it didn’t stay there. It ended up as part of the verse.

This is all theory, by the way—educated guesses from educators who guess all the time and sound quite smart while doing it.

Danged if the editor’s add-on didn’t end up in some form or another in the Vulgate Bible (birthday, late AD 300s).

That’s a Latin translation revered by Catholics from pope to peon. Latin was the native language of the Romans.

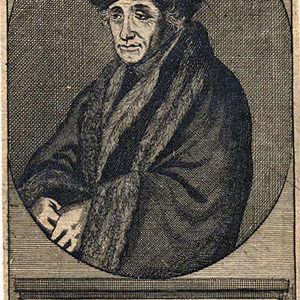

When a Catholic priest named Erasmus (1466-1536) decided to put the New Testament back into its original language of Greek, he lost a bet. To pay up, he had to include this inflated verse in his translation—which he did, adding a note of protest. He pulled the phrase from later editions of the New Testament.

Sadly, KJV translators in the early 1600s based their work on a lost bet: material that drew from one of Erasmus’ early editions.

That’s how the phrase wormed its way into the KJV Bible which, ironically, needs edited because of it. That’s if the majority opinion of Bibles is any indication.

Scholars translating Bibles today have older, more reliable copies of the New Testament to draw from. Some date back to the AD 100s.

Pitifully few of those old copies picked up that editor’s phrase, which scholars call the Comma Johanneum, and we normal people might call the Trinity Add-on. Or maybe John’s Comma Inserted by a Clueless Editor.

Out of thousands of ancient copies of the New Testament, the Trinity Add-on appears in three, oddly enough. From centuries 12, 15, and 16.

Those three, scholars say, were inserted by scribes who drew from the Latin Vulgate translation instead of copies made from older Greek editions.

What a great story — and something I’ve always wondered about. Thanks for all the research and background, Steve!

Thanks for the idea, Steve. I didn’t know the background on this until you gave me the idea and I did a little digging. What I’m curious about now is what bet Erasmus lost…if anyone knows at this point.

Funny enough, “…of the Father and of the Son and of the Holy Spirit” in Matthew 28:19 is not immune from charges of being a later addition either. H. Benedict Green has an article devoted to this issue.

Is that missing from early manuscripts, too? The Church Fathers seemed to have agreed on the Trinity by the late 300s, as I recall. They certainly didn’t understand the Trinity, but they seemed to feel it was a clear teaching in the New Testament.

It’s not missing in early mss. (although the earliest mss. containing Matthew 28 are from the 4th century).

The ‘trinitarian’ baptism is mentioned in Justin. Green suggests it was an innovation of the 2nd century, which made its way into Matthew – being modeled after a Syrian triadic (but non-Trinitarian baptism)…or something.

Dunno if I buy his arguments (which are confusing/vague). Plus Didache 7 has a trinitarian baptism.

Excellent info. Thanks so much.